Triathlon Homes LLP v Stratford Village Development Partnership; Get Living plc; East Village Management Ltd [2024] UKFTT 26 (PC)

03 December 2024

This was one sizeable dispute, and it’s not over yet. There’s an appeal in the wings.

The issue? Who should meet the cost of remediating blocks at the Olympic Village, itself constructed for the London Olympics of 2012.

Triathlon Homes applied for a remediation contribution order under section 124, Building Safety Act 2022.

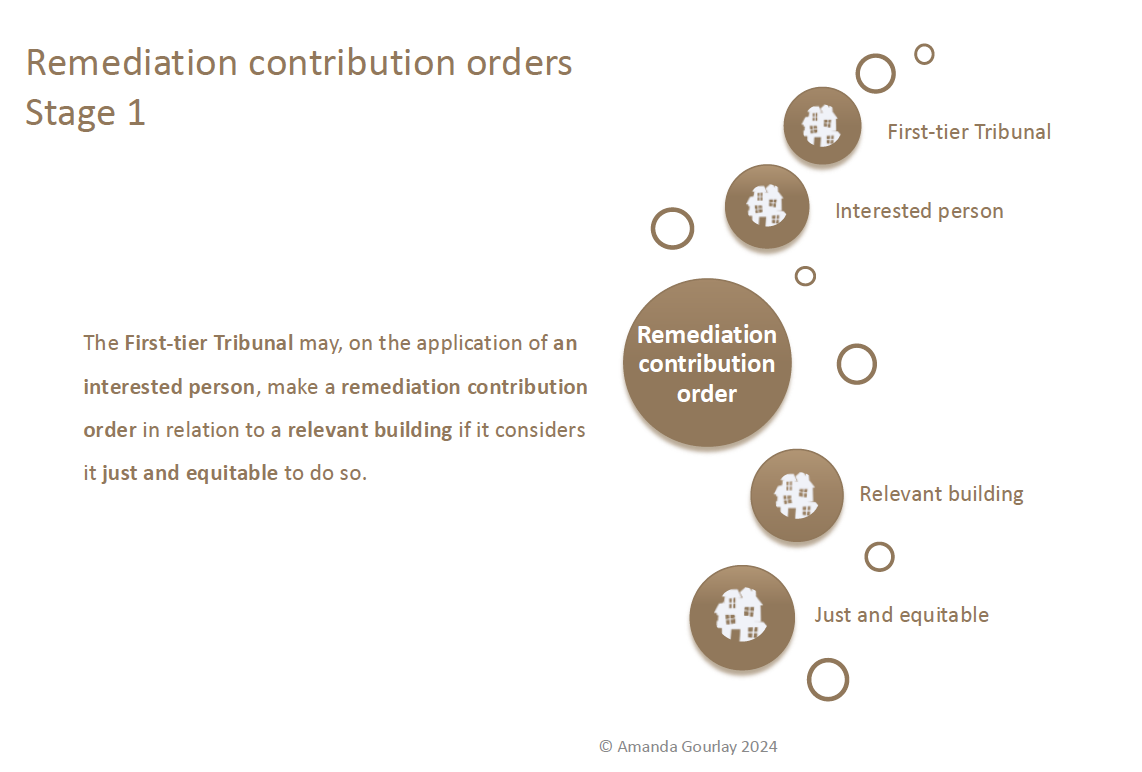

The first graphic below gives a summary of the First-tier Tribunal’s powers in relation to remediation contribution orders.

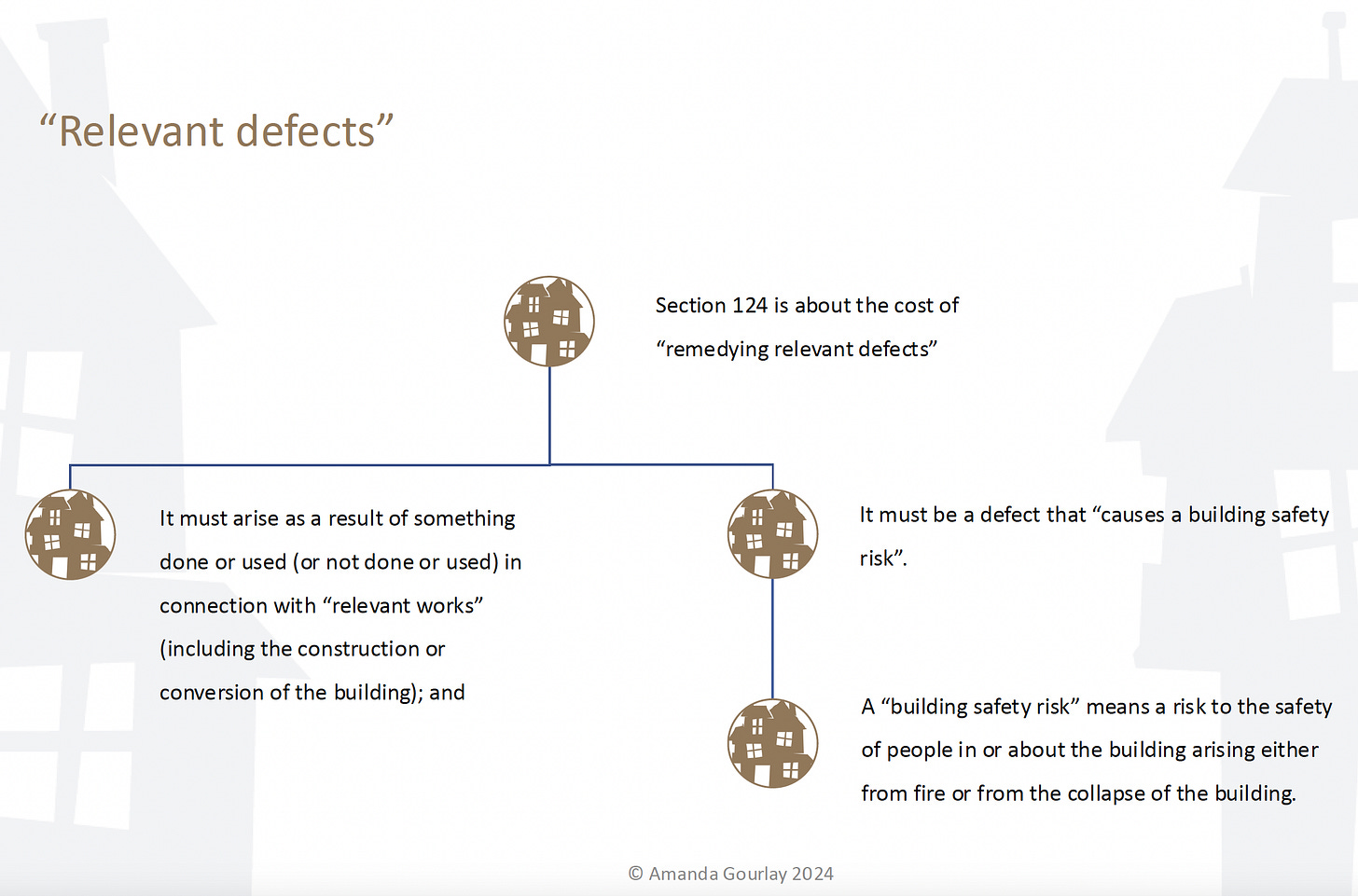

This second graphic provides more detail about what a remediation contribution order may require and from whom.

The numbers

Here are the figures:

£24.5m: Total cost of remediation work at East Village

£1.058m: Service charges paid by Triathlon

£153,538: Service charges demanded of Triathlon but not paid

£613,899: Costs and anticipated costs not yet demanded

£16.03m: Incurred or to be incurred by EVML in remedying the defects – Triathlon’s share of the total remediation costs

So large was the amount of money at stake; so complex the issues and so likely it was to be appealed that it was transferred to the Upper Tribunal under rule 25 of the FTT procedure rules.

The defects

There were serious design and construction defects in the four non-ACM external wall systems on the external façades.

Design defects found in each system, included:

combustible insulation and breather membranes in the cladding behind rainscreen panelling

inadequate/non-existent firestopping or cavity closures in some areas;

combustible timber decking and battens in external balconies,

absence or defective installation of cavity barriers and firestopping within the external wall systems.

Construction defects in the external wall systems and balconies in each Block included:

gaps between cavity barriers and external façade materials and between horizontal and vertical cavity barriers;

missing, distorted, damaged and poorly installed cavity barriers and horizontal fire barriers;

fire barriers installed directly on the combustible insulation rather than on the non-combustible substrate behind the insulation;

unidentified insulation in aluminium spandrel panels.

Retrospectivity

To my mind, this was the most significant point of principle at issue.

Section 124 of the Building Safety Act 2022 came into force on 28 June 2022.

Could a remediation contribution order be made in relation to costs incurred before that date?

Focusing on the “ordinary meaning of the words used” in section 124 of the Building Safety Act 2022, the FTT had:

“…no doubt that section 124 allows remediation contribution orders to be made in respect of costs incurred before 28 June 2022.

By section 124(2), a remediation contribution order requires payments to be made “for the purpose of meeting costs incurred or to be incurred in remedying relevant defects … In relation to time, the choice of language is unlimited, extending to costs which have already been incurred and those which are yet to be incurred… The language appears to us to be clear and explicit and the absence of any temporal limitation or transitional provision is telling.

On the contrary, it is consistent with the purpose and structure of Part 5 that the radical protection it extends to leaseholders should not be restricted by precise distinctions of time.”

In that respect, the FTT observed that the leaseholder protections contained in Part 5 of (and Schedule 8 to) the 2022 Act could not help leaseholders who had paid service charges for remediation works before 28 June 2022, because those protections were “concerned with current and future liabilities, not past payments”.

In that event, a remediation contribution order was a leaseholder’s only route to recovering service charges already paid.

The sums involved in remediation are too great, and the consequences for individuals too extreme, for … a haphazard pattern of protection to have been Parliament’s intention.

The scope of “relevant measures” and remedies

The Tribunal turned to consider the nature of a remedy.

To that end, it reminded itself of the meaning of “relevant defect” and “relevant measure” in section 120 of and paragraph 1 of Schedule 8 to the Building Safety Act 2022 respectively.

A “relevant measure” in relation to a relevant defect, means a measure taken:

(a) to remedy the relevant defect, or

(b) for the purpose of -

(i) preventing a relevant risk from materialising, or

(ii) reducing the severity of any incident resulting from a relevant risk materialising.’

Triathlon argued that it should be entitled to claim not only the costs of removing combustible cladding from the blocks and replacing it with non-combustible cladding, but also pending remediation works, the costs of:

providing a waking watch and

employing fire evacuation officers to assist residents with limited mobility in the event of a fire, and

installing, servicing and decommissioning additional fire alarms and heat detectors as a temporary measure

The Tribunal agreed:

The word “remedy” and its variants can be applied to measures short of eliminating the existence of a defect altogether.

Section 124 should be interpreted in such a way that it focuses on the practical outcome of the things which have been done, or are to be done, rather than any interpretation which tends to narrow the scope of the remediation provisions.

We would therefore have no difficulty, whether simply as a matter of ordinary language, or additionally in view of the definition of relevant defect, in concluding that any measure which causes a building defect to cease to be a relevant defect, or which is part of a larger programme of measures for that purpose, is capable of being the subject of a remediation contribution order.

Any doubt as to whether those costs can be included in a remediation contribution order has now been resolved by section 116, Leasehold and Freehold Reform Act 2024.

The leaseholders’ evidence

In its decision, the Tribunal summarised the leaseholders’ evidence, which “illustrated the different ways in which the cladding crisis has affected private individuals”.

It did so:

“because the exceptional measures contained in the 2022 Act were intended to provide relief for individual leaseholders and we consider it important that they should not be lost sight of”.

Just and equitable

At this stage, the following matters had been established:

The qualifying conditions for making remediation contribution orders against SVDP and Get Living were met;

Relevant defects existed in the building, and

The respondents were within the classes of persons who may be specified in an order.

But that was not enough.

The Tribunal had finally reached the tricky question: was it “just and equitable” to make an order?

Section 124 gives no guidance on how the FTT is to decide whether it is “just and equitable” in any particular case to make an order. Beyond stating the obvious, that the power is discretionary and should therefore be exercised having regard to the purpose of the 2022 Act and all relevant factors, it is not possible to identify a particular approach which should be taken.

The policy of the 2022 Act is that primary responsibility for the cost of remediation should fall on the original developer, and that others who have a liability to contribute may pass on the costs they incur to the developer.

That is a strong indicator that it is likely to be just and equitable for SVDP, as developer, to be ordered to pay.

Section 124 permits applications for remediation contribution orders to be made against developers and those associated with them.

If it is just and equitable to make an order against SVDP, it would also be just and equitable to make an order against Get Living, its wealthy parent, on which it depends for financial support.

That is why the Building Safety Act 2022 includes provision to capture those associated with the parties bearing primary liability.

Get Living was caught by the association provisions in section 124 because it was associated with the freeholder and each of the landlords in the chain of title.

The public purse

The Tribunal was underwhelmed by a suggestion that the Building Safety Fund, aka taxpayers, should underwrite the cost of the remediation works while Get Living litigated against others to recover the costs of those works.

Not only was Get Living a wealthy company: the legislation does not include the taxpayer in the hierarchy of those who should bear some or all of the cost of remedial work, however temporarily.

Costs incurred before 28 June 2022

Get Living was unsuccessful in arguing that it was not just and equitable to make an order including costs pre-dating the coming into force of section 124:

We have decided that the 2022 Act does permit remediation contribution orders to be made in respect of costs incurred prior to 28 June 2022. It follows that if it is otherwise just and equitable to make a remediation contribution order, the order does not cease to be just and equitable simply because it is made in respect of costs incurred prior to 28 June 2022. The legislation permits this result. Something more is required.

In principle, we can see that there might be a case where a person against whom a remediation contribution order was sought, in respect of costs incurred prior to 28 June 2022, could say that they had acted to their irretrievable prejudice, in the belief that they could safely expend the relevant funds as service charges validly demanded and received.

The conclusion

The tenor of the Tribunal’s reasoning was a clear indicator of its decision:

Drawing together all of the above analysis, including our analysis of the facts of this case, and taking into account all the relevant circumstances of this case, we conclude that it is just and equitable to make the remediation contribution orders sought by Triathlon.

We will make orders pursuant to Section 124 for the respondents to make payment to Triathlon of:

(i) the total sum of £16,031,244.53 to EVML, being the forecast cost of the Major Works and professional fees, apportioned between the Blocks in the proportions set out in paragraph 15.2 of Triathlon’s written opening submissions, and

(ii) the further total sum to EVML of £767,438.79 being costs of other remedial measures (including the forecast cost of servicing and decommissioning temporary fire alarms), and

(iii) the total sum of £1,158,358.18, by way of the additional costs.

Given the amount of money at stake and the novelty of the legislation, it is unsurprising that the parties are off to the Court of Appeal on this case in March 2025.